Targeting Subsets of Sensory Neurons

Within the nodose ganglia there are heterogeneous populations of neurons with myriad physiological functions. We use a range of techniques to target these neurons.

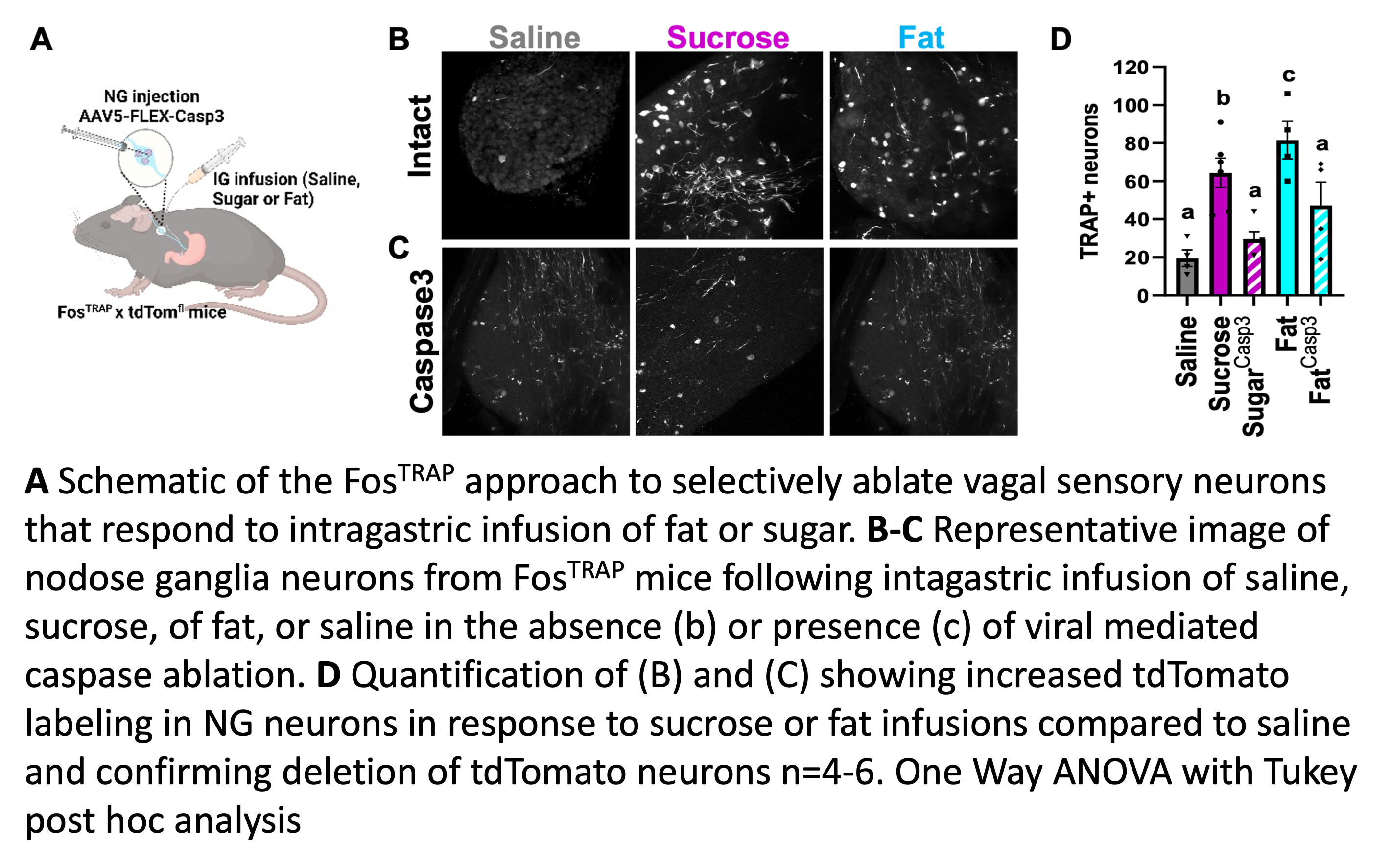

Using the FosTRAP approach we are able to target neurons based on the stimuli to which they respond. In a recent Cell Metabolism publication,1 we used the Fos-TRAP technique to selectively ablate or stimulate vagal sensory neurons that respond to intragastric infusions of fat or sugar.

We use retrograde adeno-associated virus (AAV) technology to trace the organs that the different populations of vagal sensory neurons innervate. We developed a unique, unbiased dual-viral technique for targeting sensory neurons based on the organs that they innervate, first demonstrated in a 2018 Cell paper.2 We injected a a cre-tagged retrograde virus into the gut, heart, trachea, or lung and a cre-dependent channel rhodopsin into the nodose ganglia and mapped the distinct sites in the brain to which these organ-specific neurons project.

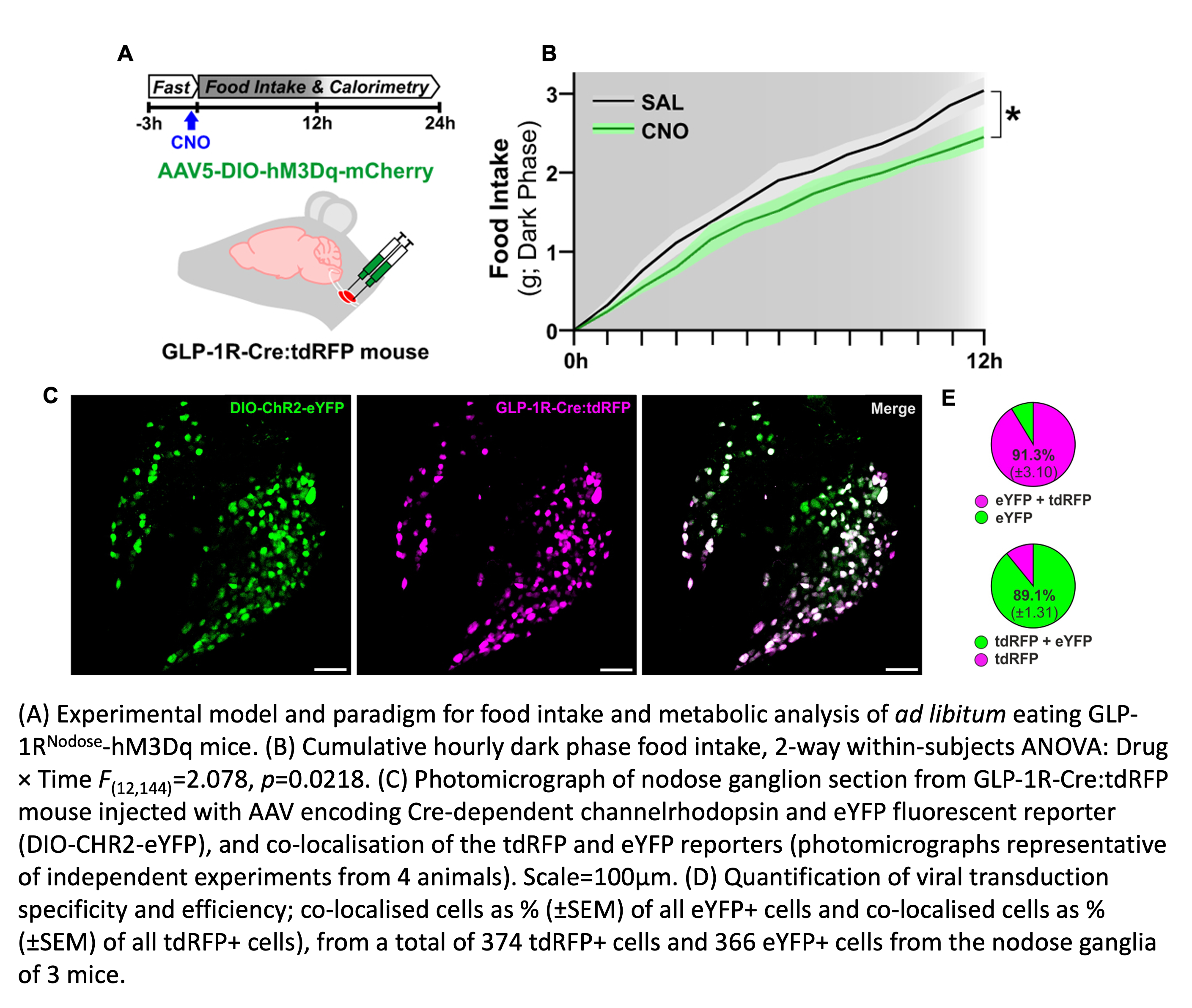

Genetic mouse lines enable us to target neurons based on the molecular markers that they express. In a study published in Nature Metabolism,3 we used a GLP1R-Cre mouse to target the vagal sensory neurons that express GLP1R, the receptor for the anorexigenic peptide glucagon-like peptide-1.

Characterizing, Mapping and Manipulating Neurons

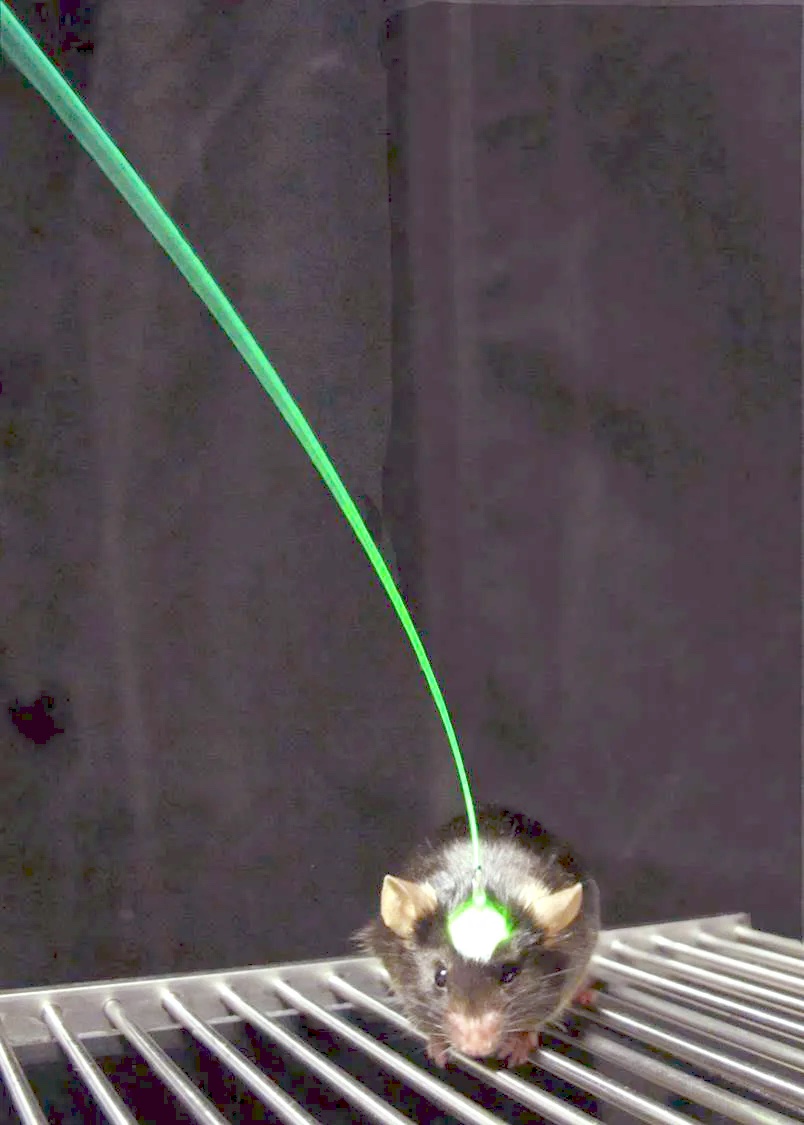

We use in vivo calcium imaging and two-photon microscopy to measure neural activity at the level of individual neurons and optogenetic and chemogenetic strategies, genetic-mediated ablation, and targeted saporin conjugates to activate and inhibit specific neuronal populations. To characterize sensory neurons we use single cell RNA sequencing, RNAscopeTM, immunohistochemistry,and quantitative PCR. We use fiber photometry and microdialysis to examine the downstream consequences of vagal sensory neuron inhibition or activation.

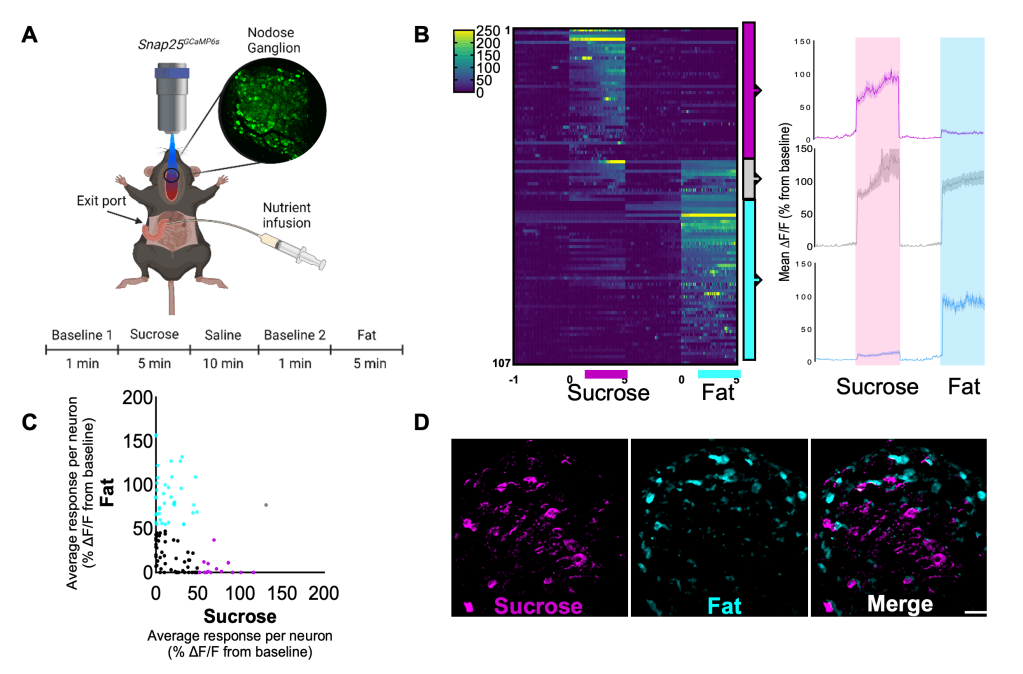

In our recent paper (image 3)1 we used calcium imaging to demonstrate that distinct vagal neuron subsets are activated in response to different nutrient stimuli.

Behavioral Neuroscience

Behavioral outcomes provide a window into the cognitive mechanisms underlying decision making. By using the BioDAQ system and lickometers, we can assess how much an animal wants to eat and what it chooses to eat. Our operant chamber setup enables us to probe motivated behaviors (e.g. place preference, progressive ratio, nose poke, and flavor-nutrient conditioning). In addition, we assess the role of learning and memory in feeding behavior using a number of mazes and tasks (e.g. food cup task, Barnes maze test, and novel object in context).

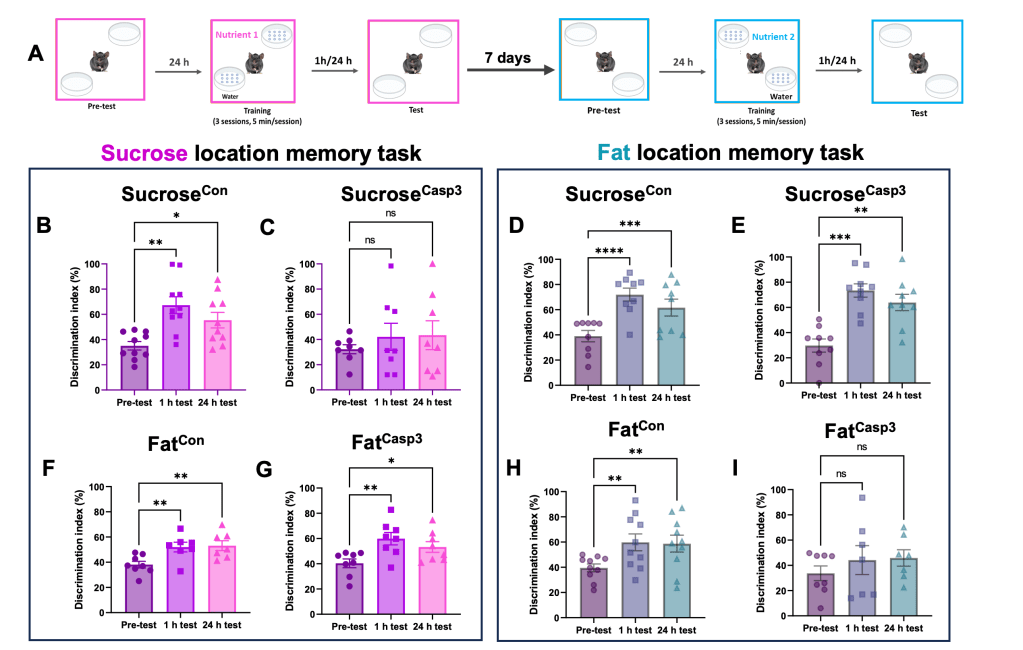

In a recent study,4 using a nutrient-specific location memory task we demonstrated that fat- and sucrose-responsive dorsal hippocampal neurons control nutrient-specific spatial memory (image 4).

References

- McDougle M, et al. Separate gut-brain circuits for fat and sugar reinforcement combine to promote overeating. Cell Metab. 2024;Jan 5:S1550-4131(23)00466-7.

- Han, W., et al. A Neural Circuit for Gut-Induced Reward. Cell 2018;175(3):665-678.

- Brierley, D. I., et al. Central and peripheral GLP-1 systems independently suppress eating. Nature Metabolism, 2021;3(2), 258-273.

- Yang, M., et al. Separate orexigenic hippocampal ensembles shape dietary choice by enhancing contextual memory and motivation. bioRxiv, 2023.10. 09.561580